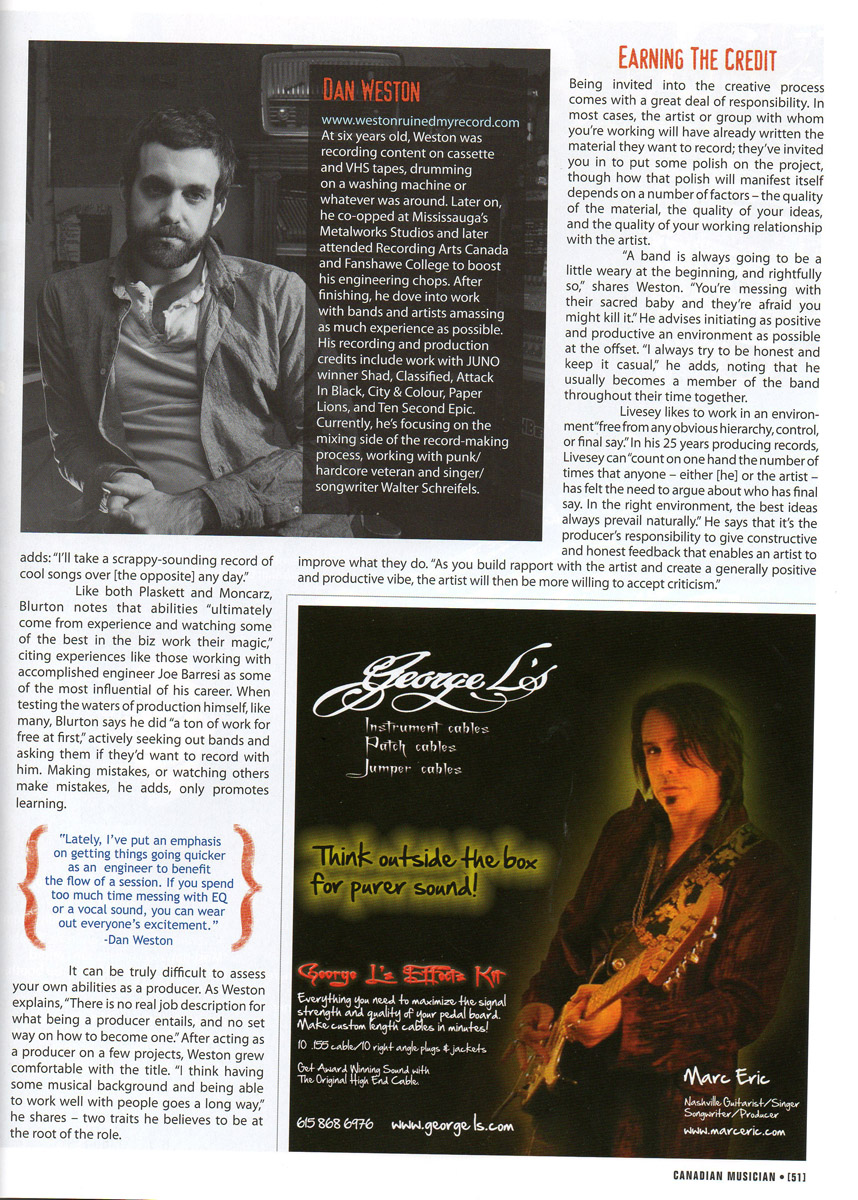

canadian musician vol. XXXIII no. 5 (sept/oct 2011)

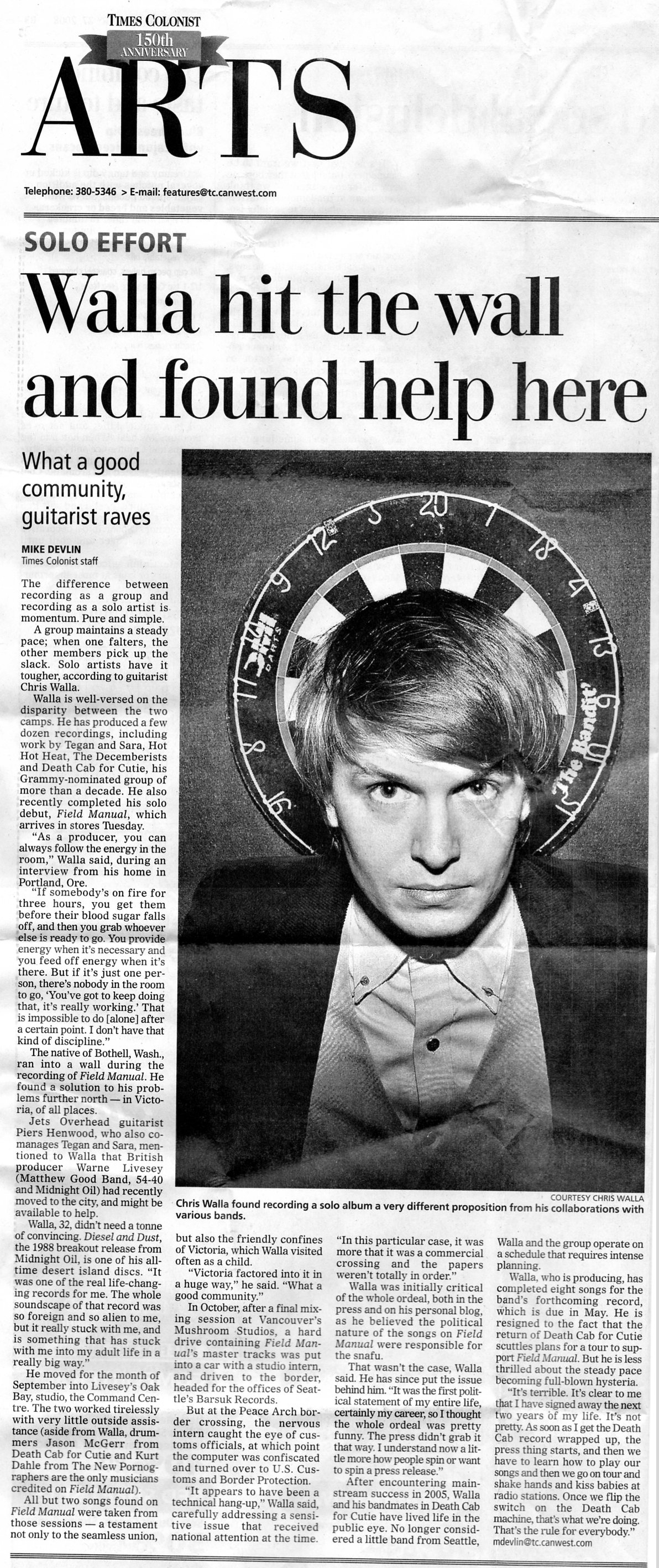

matthew good interview - by francois marchand, vancouver sun - may 29, 2011.

VANCOUVER - Matthew Good’s new album Lights of Endangered Species (out May 31) is a record 14 years in the making.

Layered with horns, strings, woodwinds, piano and acoustic guitars — most of which seem uncharacteristic for a rocker of Good’s pedigree — the album may just be his moodiest statement yet.

Over the phone from his home in Maple Ridge, Good can’t help but agree.

“Given the instrumentation and the arrangements, absolutely it is,” Good says. “The impetus for the record first came about when myself and Warne Livesey, who produced the album, were mixing [Matthew Good Band’s 1997 breakout album] Underdogs in England. I was living with him there and we were talking about what we’d like to ultimately do with regards to making a record. That conversation has always stuck with both of us for the last 13-14 years. When the band broke up [in 2002], there was a certain amount of anxiety for me and that carried over into [2003’s] Avalanche.”

The idea of making the “definitive statement” album stayed with Good throughout the past decade, a period of time marked by a divorce, battles with severe anxiety due to an undiagnosed bipolar disorder, and an addiction to Ativan that almost killed him and had him check into a psychiatric ward.

“After everything occurred in my personal life and mental illness, making Hospital Music [2007] and making Vancouver [2009] were necessities,” Good says. “They closed chapters. Having done all that, I remember after the last show in Vancouver at the Centre for Performing Arts [in 2009], me and Livesey were on the bus talking and I said, ‘You know, I’ve written this song called Set Me On Fire. It’s time we make that record that we talked about.’”

Though Livesey and Good had not worked together for two albums, they both decided it was time to take a risk and make an album untethered by other people’s opinions as to if it would be “commercially viable.”

A quick spin of Good’s latest offering reveals an album that, for some, will echo the horn-driven bombast of ’80s rock, Good seemingly channelling his socio-political and personal commentary via the textures of Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins (What If I Can’t See the Stars Mildred?, In A Place of Lesser Men) and spinning a few Daniel Lanois-esque loops (Shallow’s Low) in the process.

There is the bombast of Zero Orchestra, the pain of Set Me On Fire, the epic uplift of Non Populus and a nod to poet Emma Lazarus, whose famous text “The New Colossus” appears on a plaque at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, on the album’s title track.

But if Lights of Endangered Species feels like a bit of a throwback album, Good is looking to deeper influences.

“I grew up listening to big bands, from Glenn Miller to Basie,” Good says. “Session trumpet player Terry Townsend and I were talking about the end of Keep the Customer Satisfied by Simon and Garfunkel and how that’s probably one of the greatest interjections of horns at the end of a song. It just goes nuts. It’s phenomenal. On a song like Zero Orchestra it’s more influenced by that era than anything else.

“In other parts I used them more orchestrally,” he adds. “One of the things Warne and I did was that we used the Gil Evans approach on Sketches of Spain, in which he added a French horn. I’ve always been influenced by the squeezebox textures Tom Waits gets, and there’s a little bit of that at the end of Lights of Endangered Species. I was also very enamoured by that fantastic droning of how they’re used with regards to jazz in New Orleans. This is the first record I’ve ever used horns for and the first time I’ve ever written for horns. So it has nothing to do with ’80s pop at all. All my influences are from the ’30s and ’40s and into modern jazz — Miles Davis, Mingus and the rest.”

Good readily admits his first foray into writing and recording horns and woodwinds was challenging.

Good and Livesey originally attempted recording the horn parts with a group of Vancouver-based musicians, which yielded “horrifying” results.

Good then heard of Nashville vet Townsend via (“of all people,” Good says) The Odds’ Craig Northey.

“It was night and day,” Good says. “Warne and I were high-fiving each other, crying the entire time. The guy just laid it down.”

Townsend in turn got in touch with a few other horn experts he knew and invited them to join on the recording.

The end result definitely feels like a departure for Good.

“Ultimately, you don’t know what you’re going to get,” Good says when asked if the album fits his original vision. “You hear it in your head but that was 14 years ago. I’m far more experienced now than I was then. So what I heard in my head now was what I heard now given all the internal and external ramifications in my life. And that’s what ultimately ended up being these nine songs.

“In 1996, I wouldn’t have thought my daughter would’ve wandered downstairs while I was tracking vocals on a demo saying, ‘Hey dad, let me sing.’ And she ended up singing this bit that was so great that I used it and it’s all through Shallow’s Low.”

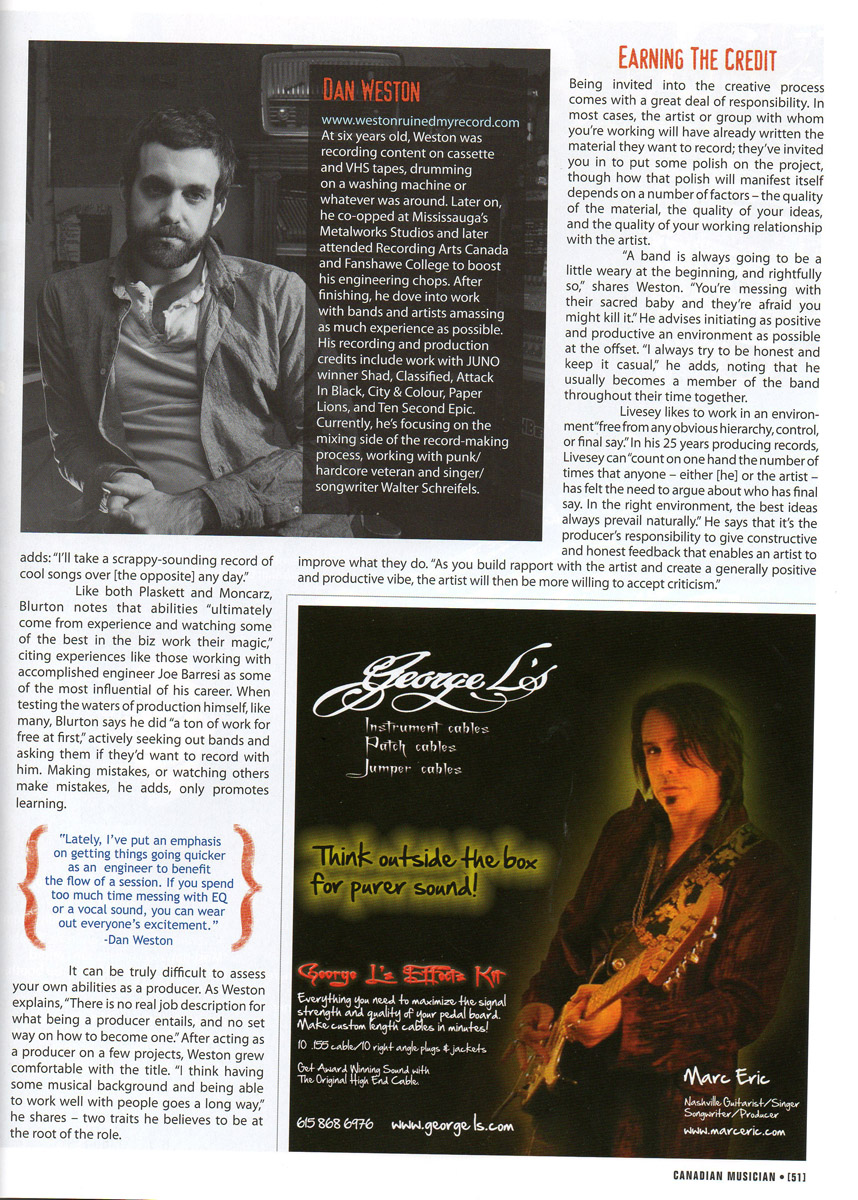

WARNE LIVESEY : BRIDGING ARTISTS AND MAGIC FOR OVER TWO DECADES

by Paul Regelbrugge

In the recording industry, the producer is generally a medium between artist and realization of the artist’s vision; between artist and ultimate record. A skilled producer is afforded the unique perspective, and often times the burden of divining the artist’s most intimate expressions of his/her intentions, and bears the ultimate task of helping to bring such dreams into relief.

Warne Livesey is one of the most outstanding producers who mine the terrain of crafting the proverbial “big rock sound.” Yet, like atmospheric greats TIM FRIESE-GREENE, HUGH JONES or DANIEL LANOIS, he offers so much more. Livesey is masterful at catapulting musical performances that convey the totality of human emotions. From the resplendent beauty abound on THE HOUSE OF LOVE’s Babe Rainbow, MATTHEW GOOD’s Avalanche, and new head-spinning New Brunswick wonders, IN-FLIGHT SAFETY, to the cathartic urgency of THE THE’s Mind Bomb, Good’s White Light Rock & Roll Review and the emotional juggernaut that is WHIPPING BOY’s Heartworm, Livesey applies darkness and light, quiet and loud like few others. Indeed, other records may boast similarly emphatic, fat drums; big, booming bass; unbelievable vocal performances; organic orchestration; and wicked guitars. One will rarely hear, however, records produced by others that are as coherent, as intelligently arranged, as dynamic and as majestically shifting from bombastic to subtle; from powerful to feather-tickling. In sum, there are countless moments of breath-taking magic in virtually every Livesey-produced record.

Livesey, who emigrated three years ago with his wife and son from their native southwest London, England to Vancouver, was kind enough to discuss various aspects of his career. He has been producing, engineering, mixing, writing and contributing musical performances since the early 1980s. In addition to his numerous musical achievements, as most recently attested to by nominations for Canada’s prestigious Juno Award and for a Western Canadian Music Award for his production on Matthew Good’s phenomenal Avalanche in 2003, Livesey is also an accomplished, gifted photographer. His most recent production projects include the above-mentioned In-Flight Safety and venerable Vancouverites 54-40.

After having done production work on The The’s Infected in 1986, Livesey caught the attention of MIDNIGHT OIL, resulting in a recording relationship spanning four records, including the triple platinum-selling Diesel and Dust. “That was a situation where the label (Columbia) just got it,” said Livesey. “They heard nothing of the record until it was finished. When they did, it was so obvious to everyone what the single would be (“Beds Are Burning”).”

Working with GUY CHADWICK on The House of Love’s Babe Rainbow was a likewise prodigious, albeit more challenging experience for Livesey. Livesey describes that there are artists who, like MATT JOHNSON and Matthew Good, are very direct and know exactly what they want to do in the studio. Thus, as long as Livesey grasps what the artist wants, it is a relatively smooth, productive process. Conversely, Chadwick would arrive at ultimate ends in relatively convoluted, meandering ways. “Maybe Guy knew what he wanted, but he didn’t – or wasn’t able to vocalize it.” Livesey recalls a good deal of pressure on Chadwick because of his earlier success, exacerbated by the fact that this was his first record without original guitarist TERRY BICKERS.

Ireland’s Whipping Boy approached Livesey because, inspired by RADIOHEAD’s The Bends, they sought a similar “big rock sound,” but with orchestration. They relished the idea that, with Livesey, they wouldn’t need an outside orchestrator. Livesey recalls that the band was very ambitious in the making of Heartworm. “They really wanted to go for it, asking ‘how big can we really go?’” Having all agreed that they made an exceptional record, Livesey reckoned the band was destined for big things, having toured with hero LOU REED and achieving moderate success with “We Don’t Need Nobody Else.” Subsequently, he received new songs and he was slated and excited to produce their next record, but Livesey recalls a change in management and they simply fell out of touch with each other. Whipping Boy ultimately self-released their eponymous swan song, featuring several of the songs that they had demoed for Livesey, after having already agreed to disband.

Interestingly, Livesey’s co-writing experience with TALK TALK’s wunderkind, MARK HOLLIS, on Hollis’ self-titled, “neo-classical/modern jazz” record was “the only album I’ve been affiliated with in which I’ve got no perspective at all. I still can’t say I like it or I don’t.” Livesey leaped at the chance to collaborate with Hollis when he heard that Hollis was looking for someone with whom to write for a forthcoming record, and Livesey was on the short list. “I had no idea what to even expect – solo record or Talk Talk. But I was such a big fan, and was thrilled to get the chance.” From the beginning, it was clear that Hollis had no intentions of returning to his relatively pop roots. After spending almost two years off and on writing and rewriting, however, Livesey today views the experience as indispensable, but one of utter frustration.

“Mark is the most extreme of the meanderers I’ve worked with. We would jam around a single idea – a few bars of something, and then spend days trying every permutation of that idea only to reject it completely and try something else. It seemed aimless and intangible to me, but somehow he arrives at a place that achieves what he wants. All I could do was to keep coming up with ideas.” Ultimately, the two didn’t see eye to eye on how the various composed pieces would be presented, and Hollis opted to record the album himself, although Livesey merits five co-writing credits.

Livesey is most proud of having worked with artists such as PETER GARRETT, Matt Johnson and Matthew Good who have, and continue to help make a bit of a difference socially and politically in life. His production philosophy is to set no predetermined direction, but rather enable artists to achieve their vision. Though he would “love to have gotten that call from Radiohead,” he thoroughly enjoys currently working with artists like Good, who is a “moving target. He is very driven, and unafraid to venture into unknown territory. You can’t be creative if you repeat what you’ve already done.

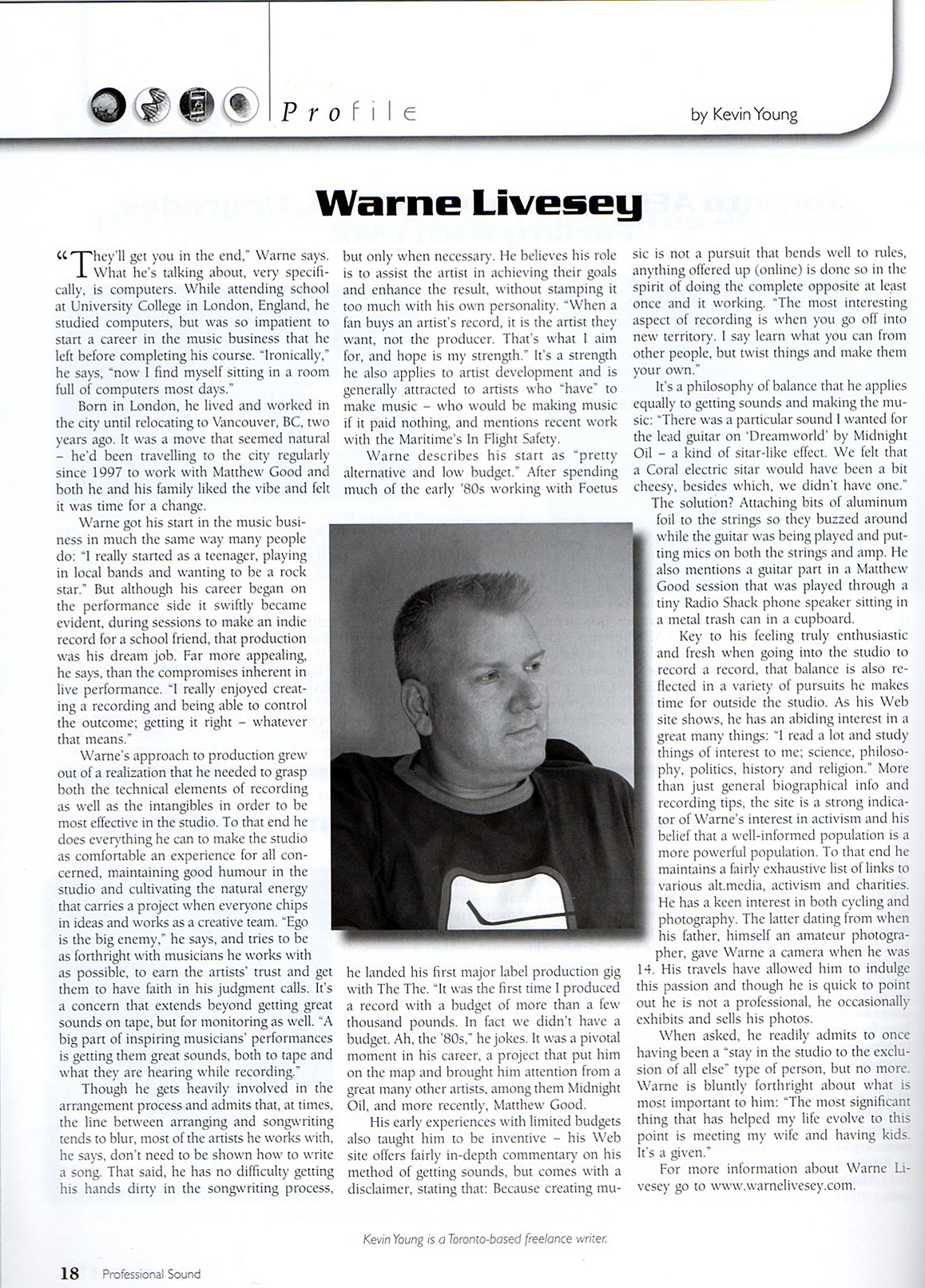

WARNE LIVESEY

by Kevin Young

“They’ll get you in the end,” Warne says. What he’s talking about, very specifically, is computers. While attending school at University College in London, England, he studied computers, but was so impatient to start a career in the music business that he left before completing his course. “Ironically,” he says, “now I find myself sitting in a room full of computers most days.”

Born in London, he lived and worked in the city until relocating to Vancouver, BC, two years ago. It was a move that seemed natural – he’d been travelling to the city regularly since 1997 to work with Matthew Good and both he and his family liked the vibe and felt it was time for a change.

Warne got his start in the music business in much the same way many people do: “I really started as a teenager, playing in local bands and wanting to be a rock star.” But although his career began on the performance side it swiftly became evident, during sessions to make an indie record for a school friend, that production was his dream job. Far more appealing, he says, than the compromises inherent in live performance. “I really enjoyed creating a recording and being able to control the outcome; getting it right – whatever that means.”

Warne’s approach to production grew out of a realization that he needed to grasp both the technical elements of recording as well as the intangibles in order to be most effective in the studio. To that end he does everything he can to make the studio as comfortable an experience for all concerned, maintaining good humour in the studio and cultivating the natural energy that carries a project when everyone chips in ideas and works as a creative team. “Ego is the big enemy,” he says, and tries to be as forthright with musicians he works with as possible, to earn the artists’ trust and get them to have faith in his judgment calls. It’s a concern that extends beyond getting great sounds on tape, but for monitoring as well. “A big part of inspiring musicians performances is getting them great sounds, both to tape and what they are hearing while recording.”

Though he gets heavily involved in the arrangement process and admits that, at times, the line between arranging and songwriting tends to blur, most of the artists he works with, he says, don’t need to be shown how to write a song. That said, he has no difficulty getting his hands dirty in the songwriting process, but only when necessary. He believes his role is to assist the artist in achieving their goals and enhance the result, without stamping it too much with his own personality. “When a fan buys an artist's record, it is the artist they want, not the producer. That's what I aim for, and hope is my strength.” It’s a strength he also applies to artist development and is generally attracted to artists who “have” to make music – who would be making music if it paid nothing, and mentions recent work with the Maritime’s In Flight Safety.

Warne describes his start as “pretty alternative and low budget.” After spending much of the early ’80s working with Foetus he landed his first major label production gig with The The. “It was the first time I produced a record with a budget of more than a few thousand pounds. In fact we didn't have a budget. Ah, the ’80s,” he jokes. It was a pivotal moment in his career, a project that put him on the map and brought him attention from a great many other artists, among them Midnight Oil, and more recently, Matthew Good.

His early experiences with limited budgets also taught him to be inventive – his Web site offers fairly in-depth commentary on his method of getting sounds, but comes with a disclaimer, stating that: Because creating music is not a pursuit that bends well to rules, anything offered up (online) is done so in the spirit of doing the complete opposite at least once and it working. “The most interesting aspect of recording is when you go off into new territory. I say learn what you can from other people, but twist things and make them your own.”

It’s a philosophy of balance that he applies equally to getting sounds and making the music: “There was a particular sound I wanted for the lead guitar on ‘Dreamworld’ by Midnight Oil – a kind of sitar-like effect. We felt that a Coral electric sitar would have been a bit cheesy, besides which, we didn't have one.” The solution? Attaching bits of aluminum foil to the strings so they buzzed around while the guitar was being played and putting mics on both the strings and amp. He also mentions a guitar part in a Matthew Good session that was played through a tiny Radio Shack phone speaker sitting in a metal trash can in a cupboard.

Key to his feeling truly enthusiastic and fresh when going into the studio to record a record, that balance is also reflected in a variety of pursuits he makes time for outside the studio. As his Web site shows, he has an abiding interest in a great many things: “I read a lot and study things of interest to me; science, philosophy, politics, history and religion.” More than just general biographical info and recording tips, the site is a strong indicator of Warne’s interest in activism and his belief that a well-informed population is a more powerful population. To that end he maintains a fairly exhaustive list of links to various alt.media, activism and charities. He has a keen interest in both cycling and photography. The latter dating from when his father, himself an amateur photographer, gave Warne a camera when he was 14. His travels have allowed him to indulge this passion and though he is quick to point out he is not a professional, he occasionally exhibits and sells his photos.

When asked, he readily admits to once having been a “stay in the studio to the exclusion of all else” type of person, but no more. Warne is bluntly forthright about what is most important to him: “The most significant thing that has helped my life evolve to this point is meeting my wife and having kids. It’s a given.”

Kevin Young is a Toronto-based freelance writer.